Battery storage is rapidly becoming a cornerstone of modern grids — for load shifting, frequency regulation, and helping balance intermittent renewables. But designing a robust financial model for a BESS project takes discipline, clarity, and sector-specific insight. Below are the building blocks and best practices to help modellers structure a model that stands up to lenders, investors, and operational realities. 🌍📊⚡

1. Define the Project Scope Clearly

- Battery capacity & power: Separate MW rating (power) from MWh rating (energy storage duration). These are often conflated but have distinct cost & revenue drivers.

- Use‐cases / services: Will your BESS be used for arbitrage, peak shaving (using stored energy to reduce grid demand during costly peak periods), ancillary services (e.g. frequency response), capacity markets, or renewables integration? Revenue streams differ, as do risk profiles.

- Lifespan & degradation: Batteries degrade. Understand cycle life, depth of discharge, round‐trip efficiency, and how these degrade over years.

🔋📈📉

2. Revenue Modelling: Multiple Streams & Uncertainty

- Energy arbitrage: Buying electricity when cheap, selling when expensive. Requires hourly or sub‐hourly price data.

- Ancillary services & capacity payments: Fees for grid stability, frequency response, reserve. These often have fixed contracts or tenders — lower volatility, but policy risk.

- Demand charges / TOU (Time-of-Use) rates: If the site is paying peak demand charges, modelling how battery dispatch can reduce demand charges matters.

You’ll want to build scenarios: base, optimistic, pessimistic, to test how sensitive IRR and NPV are to price volatility, regulation changes, and capacity derating. 📊🔮⚖️

3. Cost Structure & CAPEX / OPEX Detail

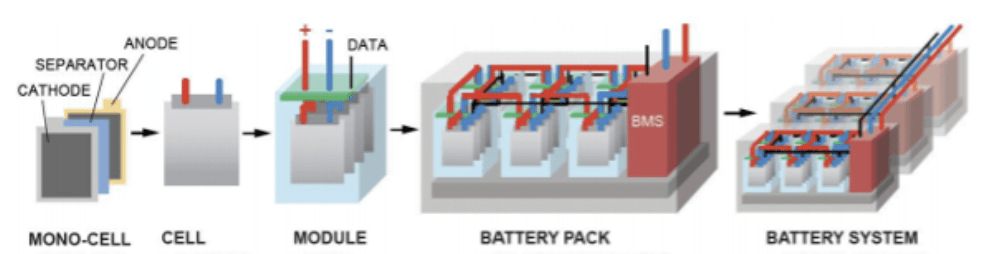

- CAPEX: Should include battery modules, power conversion systems (PCS – the inverters and related equipment that convert DC battery output to AC for the grid), grid connection, civil works, land or lease costs, permitting, etc. Often battery modules are major cost but not the only cost.

- OPEX: Maintenance (battery management systems, inverter servicing, cooling, safety), insurance, land/lease, labour, degradation replacement costs.

- Replacement & refurbishment: If parts like inverters or battery modules need partial replacement during the project life (10+ years, with typical battery module lifespan ranging from 8 to 12 years depending on chemistry and usage), plan for these.

💰⚡🔧

4. Financial Structure

- Capital financing: Equity vs debt mix, interest rates, loan tenors. Battery projects often require shorter debt tenors because technology risk is still considered higher than for, say, solar PV. Different technologies are currently used in BESS projects, such as lithium-ion (dominant today), flow batteries, sodium-sulfur, and emerging solid-state solutions, each with its own cost, performance, and risk profile.

- Depreciation, tax incentives & subsidies: Many jurisdictions grant tax credits, accelerated depreciation, or grants for storage. Model these carefully.

- Discount rates & risk adjustments: Use weighted average cost of capital (WACC) appropriate to the country & technology risk. For longer lived assets, inflation and operation assumptions matter.

🏦📉📑

5. Key Metrics: IRR, NPV, Payback & Sensitivity

- NPV (Net Present Value): Captures value over time – important if revenues & costs change yearly (e.g. worsening degradation, changing power prices).

- IRR (Internal Rate of Return) and equity IRR vs project IRR: Different depending on the leverage.

- Payback period: How many years till cumulative cashflow turns positive. Helps non‐financial stakeholders.

Sensitivity analysis: Vary key assumptions (electricity price, round‐trip efficiency, battery degradation rate, CAPEX) to see how outputs like IRR or debt service coverage ratio respond.

📊📉📈

6. Risk Factors & Mitigation

| Risk | Description | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Technology risk | Battery degradation faster than expected, lower cycle life. | Use conservative degradation curves; include replacement costs; stress test cycles. |

| Policy / regulatory risk | Subsidies or market revenues change. | Model alternative scenarios; understand contractual protections. |

| Market price risk | Electricity or energy market prices more volatile than assumed. | Use hedging or power purchase agreements; conservative forecasts; scenario analysis. |

| Operational risk | Downtime, maintenance issues, overheating, safety incidents. | Include realistic availability factors; cushion in O&M budgets. |

⚠️🔋🛡️

7. Use Tools & Templates

You don’t always need to build every model from scratch. A good excel template can help you standardize inputs, allow scenario‐comparisons, and speed up iterations.

One such tool is the BESS 10-Year Financial Model on Eloquens. It helps with cashflows, degradation, multiple revenue streams, and allows you to test sensitivities.

BESS 10-Year Financial Model on Eloquens

📑⚡💻

8. Final Thoughts

Building a financial model for a BESS project is rarely just number‐crunching. It requires a thoughtful blend of technical knowledge (battery chemistry, degradation, efficiency), market understanding (electricity prices, grid services), macroeconomic awareness (inflation, policy risks), and sound financial structure.

A well‐designed model shouldn’t just generate one set of numbers—it should allow you to stress test assumptions, compare scenarios, and understand sensitivity. When investors or lenders ask your IRR, they’ll often also ask: “What happens if prices drop 30%?”, “What if efficiency degrades faster?” If your model can answer those, you’re ahead.

📊🔮⚡

If you’re working on a BESS project or thinking about entering the energy storage space and want help adapting financial models (or templates) for your region or specific use case, happy to connect and share insights. 🌍📈🤝