Financing utility-scale solar PV projects in Africa has evolved significantly over the past decade. What was once perceived as a high-risk, donor-driven market is increasingly attracting commercial lenders, development finance institutions (DFIs), and institutional capital. Yet, despite declining technology costs and strong solar irradiation across the continent, financial close remains a complex and highly structured exercise 🌍⚡📊

The Context: Strong Fundamentals, Complex Execution 🌍📈⚡

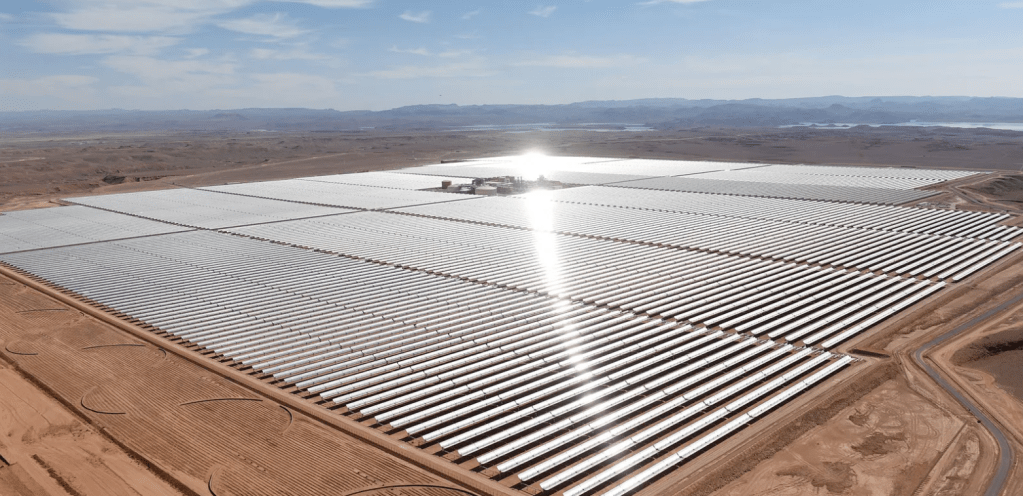

Africa hosts some of the world’s best solar resources, with capacity factors often exceeding 22–25% for fixed-tilt PV and even higher for single-axis tracking systems. From a pure energy yield perspective, the fundamentals are compelling. However, bankability is rarely driven by irradiation alone. 🌞📊🌍

Key constraints typically include:

- Offtaker creditworthiness, often linked to state-owned utilities with weak balance sheets

- Currency convertibility and FX mismatch between revenues and hard-currency debt

- Regulatory uncertainty and evolving tariff frameworks

As a result, most utility-scale solar projects (20–100 MW) still rely on blended finance structures combining DFIs, export credit agencies (ECAs), and limited commercial debt 📊⚖️🌍

Revenue Modelling: The Backbone of Bankability 📊🧮⚡

From a financial modeller’s perspective, the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) remains the single most important document driving project economics. Tariff structure, indexation mechanisms, and payment security arrangements directly feed into cash flow stability. 📄📈🔍

Typical modelling assumptions include:

- Fixed or partially indexed tariffs (USD-linked or EUR-linked where possible)

- PPA tenors of 20–25 years

- Availability-based revenue structures rather than pure merchant exposure

In practice, even small deviations in tariff indexation assumptions can materially impact project IRR. For example, a 2% annual escalation versus a flat tariff can shift equity IRR by 150–200 basis points over the life of the project. Sensitivity tables around tariff erosion, curtailment, and payment delays are therefore standard in lender-grade models 📈📊⚡

Debt Structuring: Tenor, Sculpting, and Coverage Ratios 🏦📐📊

Debt sizing for African solar projects is typically constrained by conservative Debt Service Coverage Ratios (DSCRs), often set between 1.30x and 1.40x. Loan tenors usually range from 15 to 18 years, shorter than the PPA tenor, creating a back-ended equity value profile. ⏳📉📊

Key structuring features include:

- Sculpted debt repayment aligned with projected cash flows

- Cash sweep mechanisms during high-generation periods

- Debt service reserve accounts (DSRA) covering 6 months of debt service

From a modelling standpoint, sculpting algorithms and circular references between cash flows, debt balances, and reserve accounts must be handled with precision. Errors at this stage are a common reason for delays during lender technical reviews. 🧮⚠️📊

For practitioners looking to benchmark best practices, this Solar PV financial model provides a realistic representation of how lenders typically assess solar projects: https://www.eloquens.com/tool/gyxxIMgg/finance/solar-project-financial-modeling/uk-solar-pv-excel-model?ref=finteam 🌱📊⚡

Risk Mitigation Instruments: Making Projects Investable 🛡️📉🌍

Given the structural risks, credit enhancement mechanisms are often decisive. These may include:

- Partial risk guarantees from the World Bank or regional DFIs

- Political risk insurance from providers such as MIGA or ATI

- Liquidity support facilities covering delayed PPA payments

In financial models, these instruments are not just qualitative add-ons. They directly influence DSCR assumptions, default probabilities, and, ultimately, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). A reduction of 100 bps in cost of debt can increase project NPV by several million USD on a 50 MW asset. 📉📈💰

Equity Returns and Exit Considerations 💼📊🚪

Target equity IRRs for African utility-scale solar typically range between 12% and 18% (USD-denominated), depending on country risk and contract robustness. Sponsors increasingly underwrite partial exits after COD, selling down stakes to infrastructure funds seeking long-term, de-risked yield. 📈🤝🌍

This trend has important implications for modelling:

- Clear separation between construction-phase and operational-phase risk

- Dividend distribution tests aligned with lender covenants

- Exit valuation scenarios based on contracted cash flows rather than merchant upside

Looking Ahead: Standardisation and Scale 🔭⚡📐

As more solar projects reach operation, the market is slowly converging towards greater standardisation of PPAs, financial structures, and risk allocation. This is positive news for developers and financiers alike, reducing transaction costs and accelerating deployment. 🌍📉⚡

For financial modellers, the challenge remains to translate complex contractual and risk frameworks into transparent, auditable models that can withstand scrutiny from multiple stakeholders. In Africa’s solar sector, robust financial modelling is no longer a support function — it is a decisive competitive advantage ⚡📊🌍